A shiny new city rising in the desert is designed to be a testing ground for everything from wireless networks to self-driving cars. One catch: It's totally empty.

UNITED STATES

OF INNOVATION

New Ideas, New Markets, New Insights

All around the country, Americans are dreaming big. Their boldest ideas are changing their communities--and having a ripple effect throughout the world.

CLICK HERE to read about pockets of innovation in other U.S. cities.

This summer, Pegasus Global Holdings will begin building a city from scratch in the desert just outside of Hobbs, New Mexico, that will look not unlike Hobbs itself. The Center for Innovation, Testing and Evaluation will be modeled on a mid-sized, mid-American town of about 35,000 people. Hobbs, located just outside the Texas border in the Southeastern corner of the state, is just a bit larger than that. The new city--CITE, as the locals and out-of-town developers call it--will similarly have a kind of downtown, a retail district, residential neighborhoods, and collar communities. It will have functioning roads, self-sustaining utilities, and its own communications infrastructure. It will not, however, have a single permanent resident.

After years of pursuing high-tech companies, Hobbs will be getting what might be one of the most impressive high-tech novelties around: a 15-square mile, fully functioning but empty town next door, unlike any other R&D facility in the world, that will be used to test everything about the future of smart cities, from autonomous cars to new wireless networks.

[youtube 2iDVcdxzJmo]

To Hobbs Mayor Sam Cobb, this is the culmination of three decades of a city trying to reinvent itself. Back in the mid-1980s, it first became clear that the oil and gas industry that dominates this part of the country would no longer employ quite so many people, with quite as many high-end jobs.

“Those of us that have been involved in this for these many years, we came to the realization that it was never going to be like it was before,” Cobb says. “Technology had changed it forever.” Today, Exxon no longer needs to keep 200 highly trained engineers here. An oil company drilling a well can monitor and control the entire process from miles away. “All of those things are being uploaded via satellite to an engineer who is looking on his iPad while he’s watching the football game at his home in Houston,” Cobb says. “The chances of him ever returning to Hobbs, New Mexico, are slim.”

And so the town started chasing new high-tech industry itself: uranium enrichment for nuclear power plants, biodiesel development, nanotechnology. Then earlier this year, Pegasus selected Hobbs out of 16 New Mexico communities that had vied to host this empty research city. If this facility takes off as Pegasus and state officials hope it will, CITE will become not just the largest business operation around Hobbs, but one of the most significant in the region.

“CITE is potentially a game-changer for New Mexico,” says Jon Barela, the state’s Economic Development Cabinet Secretary. He readily admits that his state is “somewhat under the radar” as a national center for innovation, but he expects that to change. “The real long-term payoff is going to be the tech transfer that will take place from CITE. We hope those companies that test and evaluate products will be eventually manufacturing those products in New Mexico.”

This empty city would address one of the great obstacles to the commercialization of new technology: that “valley of death” between early-stage R&D and the deep pockets that are willing to invest in products once they have hard data behind them. Pegasus itself develops early-stage intellectual property at that moment just after basic R&D but before prototyping. It has routinely struggled, however, to find testing beds to evaluate prototypes before they can be commercialized. As it turns out, there are not a lot of places in the world to test real-life conditions without real, live people around.

“You can’t just do it like Thomas Edison did,” says Bob Brumley, a senior managing director with Pegasus. “If Edison was living today, everything he was doing in his lab--even what Ben Franklin was doing with electricity--would be against a variety of different city, county, or state regulations. Remember Ben Franklin had his nephew out there looking at a lightning storm. Can you imagine today someone trying to do that?”

Some of Pegasus’s own subsidiaries may apply to test prototypes here (and it’s easy to envision the products of those other local high-tech companies testing here as well). But CITE will mainly be a landlord to everyone else who might want to come in, locally and internationally, including startups, universities, private corporations, and public laboratories.

Google, for instance, has been piloting autonomous cars up and down California highways. But those cars always have people in them, even if those people aren’t at the wheel. Currently, there’s nowhere to test truly autonomous--unoccupied--vehicles in urban conditions without any urbanites around. This is exactly the kind of problem CITE could solve.

Pegasus settled on this corner of New Mexico for a combination of assets that exist nowhere else in the country. Both the Los Alamos and Sandia national laboratories are based here, making New Mexico a destination for major federal investment dollars. Thanks to the labs, the area already has in place top-flight infrastructure, from fiber-optic conduit to highways. The state university system, Brumley says, is experienced in working with public labs and private businesses. And lastly, New Mexico has land. Lots of land. CITE needed a big chunk of it--in all, about 21 square miles, including the main research city, support facilities, and a buffer around it to ensure privacy for the researchers and quiet for Hobbs.

The center of Hobbs and the heart of CITE will be about 10 to 12 miles apart. As for what’s out there now, Cobb laughs: “Horses and cows.” For decades, the future site of this technology test bed has been a private, working ranch.

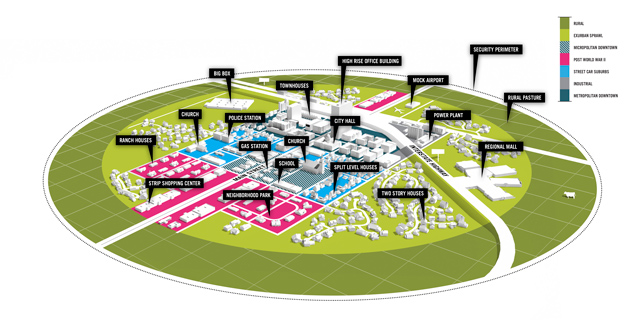

In its place, a small city will grow up along a pattern familiar to any urban planner with historic warehouses, a low-rise urban center of four- to six-story buildings, light industrial and retail zones, residential neighborhoods, inner-ring “streetcar” suburbs, exurbs, and a rural area. There will be gas stations and big-box stores, cottage-style housing, and split-level homes. And flushing toilets. “Everybody seems to be fixated on the flushing toilets,” Brumley says. Pegasus will stop shy of interior decorating. But these structures will otherwise be built to code and move-in ready. The whole idea, after all, is to replicate true-to-life cities--at least as true-to-life as cities can be without any residents around.

Pegasus designed CITE’s layout using Census data on the profile of typical cities this size. In the midst of developing the project, Brumley flew into the Charlotte airport and caught a glimpse out the window of a place that looked from above exactly like what he had been envisioning. Since then, Rock Hill, South Carolina, has served as the more literal model for the mock town that will develop outside of Hobbs.

“We never told anybody about Rock Hill,” Brumley says. “Everybody saw their own home town in that footprint. I had the dean of one of the colleges in New Mexico say, ‘That’s where I’m from, that’s Lincoln, Nebraska!’ It was amazing.”

CITE will intentionally be an imperfect place, one where everything won’t always work properly, where researchers will find more frustration than they ever do in a lab. CITE will not be a “smart” city in the desert, as many planners and engineers may dream of constructing from scratch. “We’re a dumb city,” Brumley says, “and we bring smart technology to the dumb city, or the ‘legacy’ city, to see how its IQ can be elevated. If you think of it that way, 99.9 percent of all American cities are dumb--they’re all legacy.”

And this, he says, is one of the big questions of our times: How do we effectively spend billions of public dollars needed to make our cities smarter, more efficient, and sustainable, if we don’t know for certain exactly which technologies will do the job? Those questions, he hopes, can be answered here.

Next door, the people of Hobbs stand to benefit in multiple ways. CITE will of course bring jobs: 350 permanent ones and 10 times that many in the design, construction, and development of the place. Cities both produce and consume resources, and CITE will essentially be a resource producer with no consumers, meaning that it will have excess utilities to sell in bulk to the local community. Hobbs may also be transformed by all of the innovators who will come here.

“The permanent employees are going to become part of the fabric of our community,” Cobb says. “They’ll be involved in our schools, our churches. They’ll be involved in civic organizations.”

As a result, the people of Hobbs will also likely learn about many of the ideas to come out of CITE before the rest of us do. This testing town isn’t supposed to be a tourist destination. “This is a serious place for serious people doing serious work,” Brumley says. But neither will it be a secret facility. And if anyone gets to take a peek, the people of Hobbs will. After all, Brumley is just as interested in ensuring the community understands the value of this facility as Hobbs is in luring places like this to town.

Follow the conversation on Twitter using the tag #USInnovation.

DIGITAL JUICE

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank's!