Nilpotent and Solvable Lie Algebras:

There are two big types of Lie algebras that we want to take care of right up front, and both of them are defined similarly. We

remember that if

and

are ideals of a Lie algebra

, then

![[I,J] [I,J]](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BI%2CJ%5D&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

— the collection spanned by brackets of elements of

and

— is also an ideal of

. And since the bracket of any element of

with any element of

is back in

, we can see that

![[I,J]\subseteq I [I,J]\subseteq I](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BI%2CJ%5D%5Csubseteq+I&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

. Similarly we conclude

![[I,J]\subseteq J [I,J]\subseteq J](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BI%2CJ%5D%5Csubseteq+J&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

, so

![[I,J]\subseteq I\cap J [I,J]\subseteq I\cap J](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BI%2CJ%5D%5Csubseteq+I%5Ccap+J&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

.

Now, starting from

we can build up a tower of ideals starting with

and moving down by

![L^{(n+1)}=[L^{(n)},L^{(n)}]\subseteq L^{(n)} L^{(n+1)}=[L^{(n)},L^{(n)}]\subseteq L^{(n)}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=L%5E%7B%28n%2B1%29%7D%3D%5BL%5E%7B%28n%29%7D%2CL%5E%7B%28n%29%7D%5D%5Csubseteq+L%5E%7B%28n%29%7D&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

. We call this the “derived series” of

. If this tower eventually bottoms out at

we say that

is “solvable”. If

is abelian we see that

![L^{(1)}=[L,L]=0 L^{(1)}=[L,L]=0](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=L%5E%7B%281%29%7D%3D%5BL%2CL%5D%3D0&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

, so

is automatically solvable. At the other extreme, if

is simple — and thus not abelian — the only possibility is

![[L,L]=L [L,L]=L](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BL%2CL%5D%3DL&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

, so the derived series never gets down to

, and thus

is not solvable.

We can build up another tower, again starting with

, but this time moving down by

![L^{n+1}=[L,L^n] L^{n+1}=[L,L^n]](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=L%5E%7Bn%2B1%7D%3D%5BL%2CL%5En%5D&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

. We call this the “lower central series” or “descending central series” of

. If this tower eventually bottoms out at

we say that

is “nilpotent”. Just as above we see that abelian Lie algebras are automatically nilpotent, while simple Lie algebras are never nilpotent.

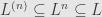

It’s not too hard to see that

for all

. Indeed,

to start. Then if

then

![\displaystyle\begin{aligned}L^{(n+1)}&\subseteq [L^{(n)},L^{(n)}]\\&\subseteq [L,L^n]\\&=L^{n+1}\end{aligned} \displaystyle\begin{aligned}L^{(n+1)}&\subseteq [L^{(n)},L^{(n)}]\\&\subseteq [L,L^n]\\&=L^{n+1}\end{aligned}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7DL%5E%7B%28n%2B1%29%7D%26%5Csubseteq+%5BL%5E%7B%28n%29%7D%2CL%5E%7B%28n%29%7D%5D%5C%5C%26%5Csubseteq+%5BL%2CL%5En%5D%5C%5C%26%3DL%5E%7Bn%2B1%7D%5Cend%7Baligned%7D&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

so the assertion follows by induction. Thus we see that any nilpotent algebra is solvable, but solvable algebras are not necessarily nilpotent.

As some explicit examples, we

look back at the algebras

and

. The second, as we might guess, is nilpotent, and thus solvable. The first, though, is merely solvable.

First, let’s check that

is nilpotent. The obvious basis consists of all the matrix entries

with

, and we can know that

![\displaystyle[e_{ij},e_{kl}]=\delta_{jk}e_{il} \displaystyle[e_{ij},e_{kl}]=\delta_{jk}e_{il}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle%5Be_%7Bij%7D%2Ce_%7Bkl%7D%5D%3D%5Cdelta_%7Bjk%7De_%7Bil%7D&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

We have an obvious sense of the “level” of an element: the difference

, which is well-defined on each basis element. We can tell that the bracket of two basis elements gives either zero or another basis element whose level is the sum of the levels of the first two basis elements. The ideal

is spanned by all the basis elements of level

. The ideal

is then spanned by basis elements of level

. And so it goes, each

spanned by basis elements of level

. But this must run out soon enough, since the highest possible level is

. In terms of the matrix, elements of

are zero everywhere on or below the diagonal; elements of

are also zero one row above the diagonal; and so on, each step pushing the nonzero elements “off the edge” to the upper-right of the matrix. Thus

is nilpotent, and thus solvable as well.

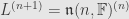

Turning to

, we already know that

![L^{(1)}=[L,L]=\mathfrak{n}(n,\mathbb{F}) L^{(1)}=[L,L]=\mathfrak{n}(n,\mathbb{F})](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=L%5E%7B%281%29%7D%3D%5BL%2CL%5D%3D%5Cmathfrak%7Bn%7D%28n%2C%5Cmathbb%7BF%7D%29&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

, which we just showed to be solvable! We see that

, which will eventually bottom out at

, thus

is solvable as well. However, we can also calculate that

![\displaystyle\begin{aligned}L^2&=[L,L^1]\\&=[\mathfrak{t}(n,\mathbb{F}),\mathfrak{n}(n,\mathbb{F})]\\&=\mathfrak{n}(n,\mathbb{F})\\&=L^1\end{aligned} \displaystyle\begin{aligned}L^2&=[L,L^1]\\&=[\mathfrak{t}(n,\mathbb{F}),\mathfrak{n}(n,\mathbb{F})]\\&=\mathfrak{n}(n,\mathbb{F})\\&=L^1\end{aligned}](http://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7DL%5E2%26%3D%5BL%2CL%5E1%5D%5C%5C%26%3D%5B%5Cmathfrak%7Bt%7D%28n%2C%5Cmathbb%7BF%7D%29%2C%5Cmathfrak%7Bn%7D%28n%2C%5Cmathbb%7BF%7D%29%5D%5C%5C%26%3D%5Cmathfrak%7Bn%7D%28n%2C%5Cmathbb%7BF%7D%29%5C%5C%26%3DL%5E1%5Cend%7Baligned%7D&bg=e6e6e6&fg=333333&s=0)

and so the derived series of

stops after the first term and never reaches

. Thus this algebra is solvable, but not nilpotent.

DIGITAL JUICE

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank's!