Some of the most interesting revitalization work in Savannah is coming not from the traditional--and often unsuccessful--saviors of decayed neighborhoods. It’s coming from design students, who are earnestly trying to find ways to work with local residents without igniting suspicion of outsiders wielding big ideas.

UNITED STATES

OF INNOVATION

New Ideas, New Markets, New Insights

All around the country, Americans are dreaming big. Their boldest ideas are changing their communities--and having a ripple effect throughout the world.

CLICK HERE to read about unexpected pockets of innovation in other cities.

In a city famously built around its public squares, Savannah’s Waters Avenue doesn’t have any. The neighborhood, which runs the length of about 25 blocks along what was once a thriving thoroughfare, is today short on a lot of community assets. Businesses have dried up. And though the homeownership rate is high, many of the modest single-family homes adjoin boarded-up buildings. The whole neighborhood, located east of downtown, has over the years been battered by redlining, white flight, and botched urban renewal. “It looks like a neighborhood,” resident Jerome Meadows says, “that has been pushed to the brink.”

The Savannah city government targeted Waters Avenue two years ago for revitalization (that process, though, is inching along at the pace of what locals politely refer to as “Slowvannah”). But some of the most interesting work here is coming not from the traditional--and often unsuccessful--saviors of decayed neighborhoods. Nor is it coming from government bureaucrats or economic development gurus or big business interests. It’s coming from design students at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), who are earnestly trying to find ways to work with Waters Avenue residents without igniting suspicion of outsiders wielding big ideas.

Watch a slideshow about SCAD's revitalization efforts here.

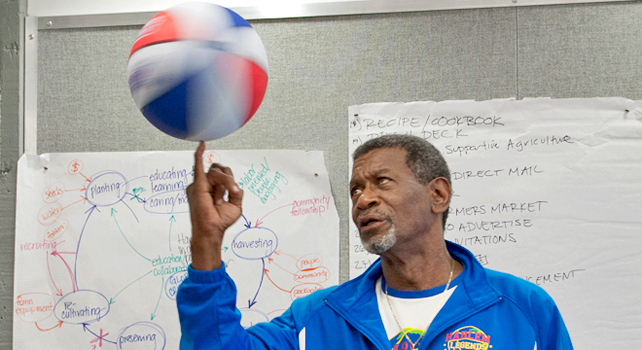

The challenge is an old one in urban areas across the country: How do you resuscitate a community without condescending to it, while ensuring that long-time residents won't be pushed aside, or worse, priced out? The partnership here in Savannah, though, is a particularly unlikely one, pairing the well-off students of a pricey art and design school with the low-income, minority residents of a community with scant interest in art and design. You know that expression, Meadows asks, about preaching to the choir? There is no choir for the arts on Waters Avenue. (In reality, there is a very small one, and Meadows is it. A long-time artist, he moved his home and workspace into a historic icehouse on Waters Avenue more than a decade ago.)

“One of the difficulties when you say ‘design,’ and in particular ‘graphic design,’ is that people start saying ‘oh, logos and brochures,’” says John Waters, the chair of SCAD’s graphic design department. “But that’s not all of it. A lot of it is just concepts, it’s about thinking about a situation, and letting that thinking drive what the action is going to be.”

There have been a few logos and brochures, designed as class projects by students at SCAD for the Waters Avenue Business Association and Harambee House, a local nonprofit. But what the school is really hoping to do is to introduce the community to design thinking, to the kind of creative problem-solving that’s essential to tackling what SCAD professor Scott Boylston refers to as the intractable, “wicked problems” of any place like Waters Avenue.

“People underestimate what the creative field can do,” says Danielle Raynal, a junior at SCAD working on her BFA in graphic design. “The problems that have been there, I’m sure the business owners in the area have tried to tackle them. But what’s really absent is just creative-thinking strategies. We came in not as designers, but as creative thinkers.”

In late April, SCAD held an intensive three-day workshop--a do-ference, they called it--with design students, Waters Avenue residents, community leaders like Meadows, city officials and design thinkers from outside of town to move beyond all the disparate, 10-week class projects that have involved the community so far. SCAD’s goal wasn’t, and isn’t, to design a big solution to the community’s problems, or even to design anything tangible at all. Boylston and others want to empower Waters Avenue residents to break down and think anew about what to do with the long-shuttered high school in the neighborhood, how to give the area voice and pride through the arts, and how to amplify the power of existing assets like the business association and Harambee House.

Read and see more about the"do-ference" here.

“What you have are some very traditional attitudes about how a community can be revitalized,” Boylston says. “It must be about beautification, it must be about streetscapes, all of these kind of narrowly defined pieces that require the community to take the energy from what they already do well and pull it into a predetermined container.”

Meadows, for one, has another idea entirely. Waters Avenue clearly needs economic stimulation. But there’s a question about what comes first, he says: the cultural life of a community, or its economic vitality? “When you see the model of SoHo for example in New York City, it wasn’t Target or something like that that came in and turned SoHo around,” he says. “It was artists that were willing to come into some pretty funky spaces and create energy, create buzz. In my mind, if you can do some things to artistically make the area wake up, make people take notice, the businesses are perhaps a bit more inclined to come in, because you already have begun to draw customers they’re going to rely upon.”

Meadows has already begun working with SCAD students to create temporary, interactive sculptures in front of his studio that will, as he puts it, speak about the community and invite the community to speak back to the art. One tree-like sculpture has water droplets hanging from it containing quotes from community leaders. Passersby are invited to take smaller droplets home with them. Another piece comes with a jar of small ribbons that residents are invited to tie onto the sculpture while making a wish, creating the impression of a barren bush blooming with community input. In all of this, Meadows is aiming to generate a neighborhood dialogue. And he will be equally pleased if that dialogue consists of befuddled neighbors strolling by pondering, “What the hell is that?”

See photographs of Meadows's sculptures here.

The sculptures have been “planted” in a pair of 400-pound concrete flower planters. The city installed 40 of the planters on Waters Avenue in the 1970s as part of a beautification program, but some have since disappeared and most have fallen into disrepair. Meadows and the SCAD students now want to create a kind of adoption program for the remaining planters that would allow local businesses and groups to relocate and care for them. That is the kind of unconventional, creative idea Boylston and Waters love.

“It’s important to me,” Meadows says, “that when businesses and outside forces come in, that they at least be shown in a very forceful way that there is a culture in existence that should be utilized, that should be respected and brought into their initiative.”

At SCAD, the students and professors are all very careful to stress that they want to help the community enact its own ideas, with its own assets. The school has had a heavy hand in revitalizing much of the city over the past 30 years, buying up, renovating and moving into some 70 historic homes, warehouses, hospitals, hotels, and schoolhouses throughout Savannah. The projects on Waters Avenue will be much subtler. This whole approach--emphasizing process, not products, integrating many small ideas instead of relying on the momentum of one mega-development--will not remake the street overnight.

“But realistically, it’s the only way to do it,” Raynal says. “These are people, and they have jobs and they have other commitments. It’s something that’s really pretty intimidating to get involved with, when a group of people comes in and says they’re going to ‘revitalize’ your community. That word is pretty heavy.”

Follow the conversation on Twitter using the tag #USInnovation.

ICT4PE&D

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank's!